Adult males (stags) do bear antlers and, unusually, there may be two pairs of antlers per year. The summer antlers are the larger set, and are dropped in November following the rutting season. The second set then appear in January and are lost a few weeks later. Unique among deer, this species has antlers with a main branched anterior segment, with the points extending backwards. This deer’s summer coat is reddish tan in colour and becomes woollier and dark grey in the winter. The underside is a cream colour and along the spine there is also a distinctive darker stripe. Juveniles are spotted with pale flecks.

Did You Know

This species of deer was first made known to Western science in 1866 by Armand David (Père David), a French missionary working in China. He obtained the carcasses of an adult male, an adult female and a young male, and sent them to Paris, where the species was named Père David's Deer by Alphonse Milne-Edwards, a French biologist.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Cetartiodactyla |

| Family | Cervidae |

| Genus | Elaphurus |

| Species | davidianus |

Other Names

| English | Pere David's deer |

| French | Père David's deer |

| Chinese | Sibuxiang |

Status

This species is listed as Extinct in the Wild, as all populations are still under captive management. The captive population in China has increased in recent years, and the possibility remains that free-ranging populations can be established sometime in the near future.

Population

The first conservation reintroduction of Pere David’s deer to China included two groups, of 20 deer (5 males: 15 females) and 18 deer (all females), in 1985 and 1987, respectively. All 38 deer were donated by the Marques of Tavistock of Woburn Abbey, and the transportation was sponsored by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). The second re-introduction was carried out in August of 1986, organized by former Ministry of Forestry and WWF. A group of 39 Pere David’s deer was selected from five zoological gardens in the United Kingdom.

By the end of calving season of 2006, there were 522 E. davidianus in the Tianezhou Milu National Nature Reserve. The annual average population growth rate was 22.2%. The birth rate and population growth rate in Tianezhou were significantly higher whereas the mortality rate was significantly lower than those of the Dafeng. Currently, there are a total of 53 herds in China. Nine herds have fewer than 25 deer, 75.5% have fewer than 10 deer.

Habitat

Studies have been carried out on the behavior, ecology and reproduction of Pere David’s deer in Beijing since 1985, in Dafeng since 1986, and in Tianezhou since 2001. This species lives in low-lying grasslands and reed beds, often in seasonally flooded areas such as the lower Yangtze River valley and coastal marshes.

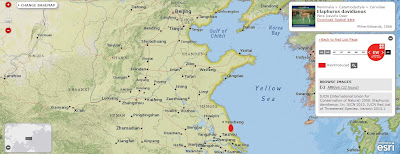

Range

During the Holocene, Pere David's deer was restricted to swamps and wetlands in the region south of 43°N and east of 110°E in mainland China. However, the distribution shrank and its population declined due to hunting and land reclamation in the swamp areas as human population expanded. Pere David's deer had largely disappeared in the wild by the late 19th century, and the last wild animal was shot near the Yellow Sea in 1939.

However, during the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911), the Nanyuang Royal Hunting Garden contained a herd of Pere David's deer in its 200 km² hunting ground. This hunting garden in the southern suburbs of Beijing was predominantly a wetland, consisting of swamps, ponds and lakes crossed by the Yongding River. However, before the demise of the royal herd of Père David’s deer in the Nanyuan Royal Hunting Garden in 1900, the deer had been introduced into private deer collections in the United Kingdom, France and Germany.

Biology

Since this deer is so rare in the wild, the only observations of its behaviour come from captive populations. It eats grass, reeds and leaves of bushes, can swim well, and spend long periods in water. It lives in single sex ormaternal herds. Animals reach maturity during second year. This species is social and lives in large herds, except before and after the breeding season, or 'rut', in June. At these times males leave the herd to feed intensively and build up strength, and before the rut, females bunch together in several groups.

A stag joins each group of females and engages in fights with rival males using its antlers, teeth and forelegs. The successful stags win dominance and, as the fittest males, are able to mate with the females. During the rutting season males do not feed, as every moment is spent trying to establish dominance over other males. Therefore, after leaving the females, males will begin feeding again and quickly regain weight. Gestation is 270-300 days. One, rarely two young are born. These are weaned in 10-11 months. Adults live up to 18 years. Data from the Dafeng Reserve suggests that female E. davidianus establish a home range of approximately 1 km².

Threats

As inhabitants of open marshland and plains, this deer was easily hunted and suffered huge population losses. In the late 19th century, the world's only herd belonged to Tongzhi, the Emperor of China. The herd was maintained in the Nanyuang Royal Hunting Garden in Nan Haizi, near Peking. In 1895, one of the walls of the hunting garden was destroyed by a heavy flood of the Yongding River, and most of the animals escaped and were killed and eaten by starving peasants. Fewer than thirty Père David's Deer remained in the garden. Then in 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion, the garden was occupied by troops and the remaining deer were shot and eaten, leaving the animal extinct in its native China.

Conservation Measures

It is listed on the Chinese Red List as Extinct in the Wild, and on the China Key List - I. Pere David, a French missionary, became fascinated by these animals and persuaded the Emperor to allow some deer to be sent to Europe. Shortly after this, in May 1865, there were catastrophic floods in China, killing the entire population of Pere David’s deer. Fortunately the captive populations in Europe bred well, and in 1986 a small group of 39 individuals was reintroduced to the Dafeng Nature Reserve in China.

The present reintroduced population within the Dafeng Nature Reserve is contained within enclosures, where it is subject to captive management and is protected from hunting. Over the years, this population has increased in numbers, and it is hoped that at some point in the future, a free-ranging population could be established in China. This species was saved from the brink of extinction and is making a slow but steady recovery. It is, however, dependant on conservation measures and captive management and so it is essential that these efforts are continued.

References